The Plight of Spirituality and the American Honeybee

In 1787, Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to George Washington saying, “Agriculture is our wisest pursuit, because it will in the end contribute most to real wealth, good morals, and happiness” (Kaminksi). Agriculture in America has come a long way since the 1700’s, and unfortunately has transformed into something quite the opposite of Jefferson’s idyllic vision.

My passion for American agriculture goes hand in hand with my passion for Buddhist philosophy. I have incorporated both into my artistic practice, exploring the negative ecological effects of American agriculture with the contrasting philosophies of non-violence and compassion in Buddhist teachings. In my mind, the philosophies of Buddhism are contradicted by the practices we have put forth in American agriculture today. Studying these topics together has informed my personal connection to nature on a spiritual level, forcing me to wonder, would the leaders of this country today make more sustainable decisions about agriculture if they were more connected to their spirituality?

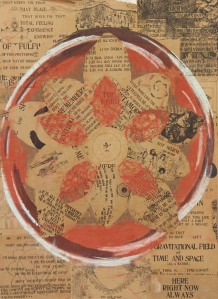

At this point in time, my studies have led me to the American honeybee, which has been mysteriously disappearing at higher rates each year. This phenomenon, known as Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), seems like a larger metaphor for the result of many years of disconnect between human beings and their spirituality. The honeybee is extremely important to agriculture because it helps pollinate one third of our crops (Sass). Through addressing the importance of the honeybee in a visual mandala, I hope to connect the viewer to the spiritual side of nature as well as draw attention to a problem that is being reflected in the ecology of the environment.

The first question I will determine is, “What is spirituality and how does it relate to nature?” Secondly, “What is the connection between spirituality and American agriculture?” To begin answering these questions, it is important to note that there is no single, widely agreed definition of spirituality. Social scientists have defined it as the search for the sacred, for that which is set apart from the ordinary and worthy of veneration (Spirituality). In Buddhist spirituality, the concern lies with the end of suffering through the enlightened understanding of reality, cultivated through wisdom and compassion (Muesse). Suffering, in Buddhist terms, can be as simple as not eating when you are hungry. If you are suffering in any way, you are hindered from seeing the world as it really is. Wisdom – seeing the world as it really is – reveals the deep interrelatedness and impermanency of all things (Muesse). When we have wisdom, we cannot help but feel compassion. This intrinsically linked combination of wisdom and compassion is how spirituality relates to nature. What I aim to answer next is: How does spirituality relate to American agriculture?

In an article by the Huffington Post, Our Spiritual Connection to Nature, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, a humanitarian, spiritual leader, and ambassador of peace and human values, talks about the connection between science and spirituality. He explains that, “Man’s knowledge of himself complements his understanding of the universe and forms the basis for a strong and healthy relationship to the creation in which he lives” (Shankar). This is where I see the connection, or rather disconnection, between spirituality and American agriculture, and further, to the American honeybee. In the livelihood of Buddhists, living compassionately means to think and act without putting ourselves at the center of the universe. In American society, agriculture is just one example of the many ways in which we have learned to act and think in self-centered ways. Our unethical and unsustainable farming methods such as monocultures and harmful pesticides have finally caught up to us, and CCD is the result.

In an article by Time magazine, The Plight of the Honeybee, Bryan Walsh discusses different views on the loss of honeybees. Tom Theobald, a beekeeper in Colorado, stated, “If we don’t make some changes soon, we’re going to see disaster. The bees are just the beginning” (Walsh, 27). Others, like journalist Hannah Nordhaus, author of the 2011 book, The Beekeeper’s Lament, wrote that, “Honeybees are the glue that holds our agricultural system together” (Walsh, 26). Walsh, who agrees with Theobald and Nordhaus, sees the loss of bees as a symbol for something even bigger: “The loss of honeybees would leave the planet poorer and hungrier, but what’s really scary is the fear that bees may be a sign that something is deeply wrong with the world around us” (Walsh, 27). Whatever the opinion is, it is widely agreed that without honeybees, life is going to get a lot harder for us.

Commercial beekeepers first started noticing the vanishing of bees from their hives in 2006. Beekeepers would open their hives and find them full of honeycomb, wax, and even honey – but no bees. Jim Doan provided one of the first documented cases of CCD. A commercial beekeeper that has been keeping bees since the age of five, Doan uncovered his bee hives and found nothing; “There were hundreds of hives in the backyard and no bees in them” (Walsh, 27). In years since, he has experienced repeated losses, his bees growing sick and dying. In order to replace lost hives, Doan had to buy new queens and split his remaining colonies. This reduced honey production and put more pressure on the few remaining healthy bees. In 2013, after decades of business, Doan gave up.

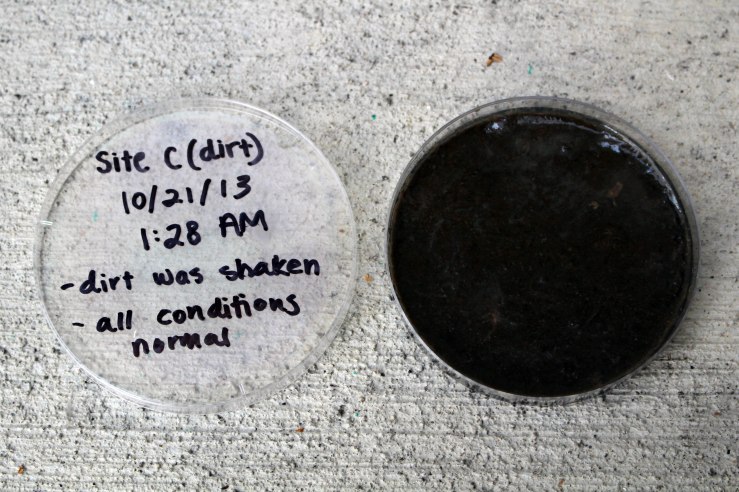

Doan is certainly not the only one that has walked out on beekeeping. Over the past 15 years, the number of commercial beekeepers has dropped by some three-quarters (Walsh, 27). While all may agree that the struggle is not worth it anymore, they differ on which of the possible causes is the most to blame. While Doan has settled on neonicotinoid pesticides, there are many other theories being studied: Nosema (a pathogenic gut fungi), Varroa mites, poor nutrition due to apiary overcrowding and increased migratory stress, and environmental stressors such as the lack of diversity in nectar/pollen, availability of only pollen and nectar with low nutritional value, and limited access to water or access to contaminated water. Although it is fair to say that CCD is caused by a combination of all the theories, I am most set on the pesticide use (specifically neonicotinoids) and environmental stressors as the primary causes.

Neonicotinoids are a class of neuro-active insecticides chemically similar to nicotine. The neonicotinoid “imidacloprid” is currently the most widely used insecticide in the world and is primarily used in agriculture (Izuru). First introduced in the 1990’s, the chemical works by interfering with the transmission of stimuli in the insect’s nervous system (Imidacloprid Technical Fact Sheet). It causes blockage in the neuronal pathway that results in the insect’s paralysis and then death (Wallingford). It is effective when the insect comes into contact with the chemical and also via swallowing. In agriculture, imidacloprid controls aphids, cane beetles, stink bugs, locusts, and a variety of other insects that damage crops. They are different than pesticides used in the past because the crop seeds are soaked in them before they are planted, rather than being sprayed on top of (Walsh, 28). Because of this, traces of the chemicals are eventually passed on to every part of the mature plant – including the pollen and nectar a bee might come into contact with – and can remain much longer than other pesticides do (Walsh, 28). According to Walsh, “The chemical is used on more than 140 different crops as well as in home gardens, meaning endless chances of exposure for any insect that alights on the treated plants” (Walsh, 27). Because of this, neonicotinoids pose a real threat to the viability of pollinators such as the honeybee.

The whole reason that harmful insecticides were even invented was because of the introduction of monocultures in the 1970’s. A monoculture is the agricultural practice of producing or growing a single crop or plant species over a wide area and for a large number of consecutive years (Kniss). An example of this would be a cornfield that stretches for miles. Because growing the same plant (and nothing else) in the same place year after year quickly depletes the nutrients that the plant relies on, chemical fertilizers are necessary to replenish the soil somehow (Altieri). The pesticides are needed because monoculture fields are highly attractive to certain weeds and insect pests. Although monocultures have been used for forty years, researchers of CCD are starting to realize that they prevent honeybees from having the diversity of nectar and pollen that they need; honeybees can travel up to five miles at a time, and monocultures may take up those five miles that the honeybee will forage (Traynor). So, to summarize, monocultures require pesticides that harm or kill honeybees, and monocultures lack the diversity of pollen and nectar that is essential to the honeybee’s natural intake.

Artists that incorporate the theme of the honeybee into their work as well as spirituality are Wolfgang Laib, Aganetha Dyck and Sarah Hatton. Laib, who incorporates natural materials into has work, has utilized materials such as milk, pollen, beeswax, rice, and marble. His works are more complex than just being about nature and the natural world; he is inspired by the purity and simplicity of Eastern philosophies, especially Zen Buddhism and Taoism. His work involves ritual, repetition, process, and a demand for contemplation; something I am trying to do too. In his famous piece, Pollen from Hazelnut, installed specifically for the MOMA’s atrium, Laib gathered pollen from around his studio and home in a small village in southern Germany:

His goal with this piece was to inseminate the minds of viewers with thoughts of harmony between human civilization and nature. He has also stated that, “Pollen is the potential beginning of the life of the plant. It is as simple, as beautiful, and as complex as this. And of course it has so many meanings. I think everybody who lives knows that pollen is important” (MoMA). Although Dyck does not use pollen, she too utilizes natural materials in her work.

His goal with this piece was to inseminate the minds of viewers with thoughts of harmony between human civilization and nature. He has also stated that, “Pollen is the potential beginning of the life of the plant. It is as simple, as beautiful, and as complex as this. And of course it has so many meanings. I think everybody who lives knows that pollen is important” (MoMA). Although Dyck does not use pollen, she too utilizes natural materials in her work.

Aganetha Dyck is a multi-media artist who works collaboratively with bees to create sculptures and drawings made up of honeycomb. Her main concern is the relationship between humans and bees, taking into account the bees’ use of their own senses; “each of her projects is to be affected by the bees’ sight, scent, vibration and movement” (Zimmer). Additionally, her work takes on different hues, textures and formations based on the bees’ pheromones, the kinds of flowers they pollinate, and type of hives they live in. One aspect of her work is adding layers to found objects such as statues and figurines and letting the bees build honeycomb around them:

Dyck’s partnership with bees helps viewers understand the importance of the pollinators, while also highlighting the exquisite beauty that happens in nature.

Dyck’s partnership with bees helps viewers understand the importance of the pollinators, while also highlighting the exquisite beauty that happens in nature.

An artist that has a very similar aesthetic approach as me is Sarah Hatton. Hatton, an artist and beekeeper, directly addresses CCD in her work. After having lost an entire colony of her own, she gathered her dead bees and coated their corpses in epoxy resin and then organized them into mathematical patterns found from patterns of nature:

Most of her works are large and reside within a circular frame. And, like myself, Hatton has a deep interest in human nature, morality, patterns, and the natural world, and balances artistry with advocacy.

Because honeybees help to pollinate one third of the human food supply, my final piece for DAAPWorks will reflect a large portion of the specific crops that will disappear if we continue our current farming practices. The piece will be an assemblage of lenticular prints that will be cut into honeycomb shapes and tiled onto a 7’ X 7’ circular wooden panel. One side of the lenticular flip will be a mandala of all of the crops the honeybee helps to pollinate, and the other side will be an image of a farmer in a monoculture field with white cut-outs of honeybees:

While some lenticulars will be transitioning from left to right, others will be transitioning from up to down. This, I hope, will be a subtle yet effective way to make the honeycomb shapes more apparent. The mandala was an important element for me because in Buddhism, mandalas are a tool for establishing a sacred place; the goal of this piece is to connect the viewer to the spirituality behind nature and agriculture, specifically focusing on honeybees and why they are important. The lenticular is important to this piece because it is a material that contradicts the spirituality that I am attempting to reveal. The lenticular requires advanced technology to be produced and reminds viewers of commercial advertising; lenticulars used to appear in cereal boxes as a “prize.” It is necessary for me to have both sides of the spectrum present, as one cannot exist without the other. The lenticular also speaks about lines and movement. The lines on the surface of the material and the movement required by the viewer to see both images reflect the nature of fast-paced mega-farming. While the lenticular forces the viewer to speed up, the mandala asks the viewer to slow down. In addition to the monoculture image present on one side of the lenticular flip, I cut out shapes of honeybees to represent the disappearance of honeybees from our landscape. Merged with the mandala image, the honeybees appear as if they are trying to form themselves into the shape of the mandala. Finally, the mandala image is more in focus than the monoculture image in order to illustrate the importance of the individual crops that the honeybee helps to pollinate.

Although Thomas Jefferson was on the right track when he envisioned “real wealth, good morals, and happiness” as the result of American agriculture, our unsustainable farming practices have steered us in the wrong direction. If we continue on this path, we risk losing our honeybees, and therefore one third of our crops. I strongly believe that if human beings were more connected to their spirituality, they would have a higher appreciation for the earth and therefore make more sustainable decisions about how to obtain food. Sri Sri Ravi Shankar puts it quite simply:

“Spirituality, the experience of one’s own nature deep within, provides the key to this vital relationship with oneself, with others and with our environment. This connection to our own essential nature eliminates negative emotions, elevates one’s consciousness and creates a spirit of care and commitment for the whole planet” (Walsh).

We need to pay attention to what our environment is telling us, and getting in touch with our spirituality is a good place to start.

Bibliography

1. Altieri, Miguel A. “Modern Agriculture: Ecological Impacts and the Possibilities for Truly Sustainable Farming.” Modern Agriculture. N.p., 30 July 2000. Web. 31 Mar. 2014. <http://nature.berkeley.edu/~miguel-alt/modern_agriculture.html>.

2. “Exhibitions: Wolfgang Laib.” MoMA. Museum of Modern Art, n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. <http://www.moma.org/visit/calendar/exhibitions/1340>

3. “Imidacloprid Technical Fact Sheet.” NPIC. Oregon State University, n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2014. <http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/imidacloprid.pdf>.

4. “Industrial Agriculture Practices: Monoculture.” Union of Concerned Scientists. Convio, 30 Aug. 2012. Web. 23 Mar. 2014. <http://www.ucsusa.org/food_and_agriculture/our-failing-food-system/industrial-agriculture/>.

5. Kaminski, John P. “The Quotable Jefferson.” Sample Chapter for Jefferson, T.; Kaminski, J.P., Ed.: The Quotable Jefferson. Princeton University Press, 27 Aug. 2007. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. <http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/s8126.html>.

6. Kniss, Andrew. “The Problem with Monoculture.” Control Freaks. N.p., 17 Aug. 2013. Web. 30 Mar. 2014. <http://weedcontrolfreaks.com/2013/08/monoculture/>.

7. Muesse, Mark W. “What Does It Mean to Lead a Spiritual Life? : A Buddhist Perspective.” Explorefaith.org. 1996-2006 Explorefaith.org, n.d. Web. 31 Mar. 2014. <http://www.explorefaith.org/steppingstones_SpiritualLife_Buddhist.htm>.

8. Sass, Jennifer. “Why We Need Bees: Nature’s Tiny Workers Put Food on Our Tables.” NRDC, Mar. 2011. Web. 31 Mar. 2014. <http://www.nrdc.org/wildlife/animals/files/bees.pdf>.

9. Shankar, Sri Sri Ravi. “Our Spiritual Connection to Nature.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc., 23 July 2010. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/sri-sri-ravi-shankar/our-spiritual-connection_b_648379.html>.

10. “Spirituality.” Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia. N.p., 12 Sept. 2013. Web. 31 Mar. 2014. <http://www.chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com/en/index.php?title=Spirituality>.

11. Traynor, Joe. “How Far Do Bees Fly? One Mile, Two, Seven? And Why?” Bee Source. Beesource.org, June 2002. Web. 31 Mar. 2014. <http://www.beesource.com/point-of-view/joe-traynor/how-far-do-bees-fly-one-mile-two-seven-and-why/>.

12. Wallingford, Anna K. “Toxicity and Field Efficacy of Four Neonicotinoids on Harlequin Bug (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae).” JSTOR. The Florida Entomologist Society, Vol. 95, No. 4. Dec. 2012. Web. 31 Mar. 2014. <http://www.jstor.org.proxy.libraries.uc.edu/stable/41759163/>

13. Walsh, Bryan. “The Plight of the Honeybee.” Time. Time, 19 Aug. 2013. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. <http://time.com/559/the-plight-of-the-honeybee/>.

14. Yamamoto, Izuru. “Nicotine to Nicotinoids: 1962 to 1997.” Nicotinoid Insecticides and the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Web. 25 Mar. 2014.

15. Zimmer, Lori. “Gallery: Aganetha Dyck Works With Live Bees To Make Beautiful Art.”Inhabitat.com. N.p., 2 Apr. 2012. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. <http://inhabitat.com/aganetha-dyck-works-with-live-bees-to-make-beautiful-art/aganetha/?extend=1>.